Download here

Humanising the Glitch

We live in a fast, digital world, yet there is a growing fascination with the handmade – slowness, tactility, and visible labour are increasingly valued. My practice explores the interplay between analogue and digital processes, asking how meaning and value shift when something is made by hand rather than by a computer. My practice revolves around “hacking” a medium by pushing materials and techniques beyond their conventional use to reveal new possibilities. By juxtaposing textiles with code, knitting with computing, and analogue processes with digital logic, I investigate the creative tension between human imperfection and machine precision.

The Jacquard loom

The Jacquard loom is an early weaving machine that exemplifies the deep historical connection between data and textile. Using a binary system of punched cards to know whether to raise or lower threads, it allowed complex patterns to be encoded into fabric, marking one of the first moments where information was stored, manipulated, and materialised through machinery. Often cited as a precursor to modern computing, the Jacquard loom reframes weaving not merely as decoration but as an act of coding, memory, and computation (Wikipedia, 2024).

The Luddite Movement

The Luddites were a group of skilled textile workers in early 19th-century England who protested against the rapid spread of mechanised looms and knitting frames that threatened their livelihoods. Active mainly between 1811 and 1817, they destroyed machinery that devalued their craftsmanship and reduced wages during a time of widespread economic hardship. Named after the mythical figure Ned Ludd, the movement was not simply anti-technology but a response to the social and economic disruptions brought by industrialisation. The British government reacted harshly, deploying troops and making machine-breaking a capital offence. Over time, “Luddite” has come to describe anyone resistant to technological change, though historically, the Luddites were less opposed to technology itself than to the ways it was used to exploit workers and erode traditional forms of skilled labour. (Wikipedia, 2025)

Just Tie Knots

My own relationship to knitting and craft is shaped by personal history. I learned knitting from my Danish grandmother, who valued precision and was taught that the back of a piece should look as perfect as the front – no knots, no loose threads, no mistakes. This mindset reflects an older approach to craft, where control, discipline, and mastery were seen as forms of respect for the material.

In recent years, however, knitting in Denmark has undergone a shift followed by many of the younger generation taking it on. Designers such as Lærke Bagger have embraced a different philosophy: “Just Tie Knots” (Bagger, 2021). This approach celebrates imperfection – the loose ends, mismatched colours, and visible joins – embracing the traces of the maker’s hand. Its growing popularity reflects a broader cultural revaluation: mistakes and irregularities are now appreciated not as flaws, but as evidence of care, time through labour, and authenticity.

Through this lens, the value and beauty of the handmade lie not in perfection, but in the small errors that reveal process, materiality, and human presence. Imperfection becomes a language, a way of making visible the labour, choices, and gestures embedded in craft.

Positions through Iterating

Edd Carr – Hacking Cyanotype

In Unit 1, my practice began to come together by experimenting with cyanotype, an early photographic printing process, and appreciating how creating images by hand felt fundamentally different from digital editing. Inspired by Edd Carr, I explored his project in which he created a music video entirely from hand-printed cyanotype frames. Carr hand-printed each frame onto paper coated for cyanotype printing and these individual prints were then digitally aligned and reassembled into an animation. Cyanotype is traditionally intended for still images, yet Carr’s work demonstrates how the medium can be “hacked” to convey motion.

At the start of Unit 2, my focus deepened to experimenting with mediums – pushing them beyond their intended use – and exploring the interplay between analogue and digital processes, investigating how each informs and transforms the other. Based on Edd Carr’s “hacking” to create movement through a still printing technique, I wanted to push this even further by seeing if I could create a sense of movement using only the hand printing technique and the cyanotype medium itself – without any digital post production involved at all.

Edd Carr’s approach encouraged me to see slowness, imperfection, and unpredictability as meaningful qualities rather than flaws, and to think about how analogue processes can reveal the human presence behind digital data. This project reaffirmed my interest in hacking mediums, working between analogue and digital systems, and finding value in the handmade as a form of resistance to digital perfection.

Positions through Contextualising

Studio work – taking on the role of a computer

My research and practice continue to explore three key themes:

“Hacking a medium”

The interplay between analogue and digital processes

The value inherent in knowing that something is made by hand

I am particularly interested in translating digital data into tactile, physical forms, taking on the role of the computer to decide what to preserve, discard, or transform. Following my cyanotype experiments, I wanted to explore the transmission of digital data further, using this approach to understand the process more deeply while reintroducing human warmth, imperfection, and presence to information that is otherwise intangible.

Underwater data cables

I began by taking an image from a website showing a map of all underwater data cables crisscrossing the globe. These invisible infrastructures constantly relay information at the speed of light, yet they remain unseen, their activity abstract and intangible. I took this image, divided it into a grid, and used my own human intuition to decide how to fill each square – each pixel. I experimented with translating this hand-pixelated version into something tactile by manually translating these pixels into knit.

Using another image of underwater cables I used the same technique but creating the pixels in either black or white based on its tone. This led me to a binary system that could then be interpreted through knitting. I explored colour, texture, and stitch choice to bring this digital code into a physical, handcrafted form. The movement of my hands mirrored the calculations of a machine, performing in minutes what a computer does in milliseconds – but with time, intention, and human presence embedded in every stitch.

Annotated bibliography

The following references and projects explore the same themes and have helped me to develop my understanding and practice.

What to Keep, What to Lose, Shaheer Tarar

Shaheer Tarar’s cross-year presentation What to Keep, What to Lose had a significant impact on the direction of my project. It offered not only a theoretical framework for thinking about digital imagery and data transmission, but also grounded these concepts through hands-on exercises that revealed the often invisible processes behind image compression and digital transformation. What stood out most to me was how clearly it exposed the decisions – both human and algorithmic – that shape the digital visuals we constantly see and take for granted.

The idea that every image is the result of decisions on “what to keep” and “what to lose” resonates strongly with my own work, which explores how digital data can be translated into tactile, human-made forms. During Tarar’s session, we were introduced to the complex layers involved in the digital image pipeline, from binary encoding and light-based transmission via fibre-optic cables, to the various levels of compression that occur along the way. It was highlighted how much information is repeatedly shaved away in this process – lossy compression algorithms deciding, based on pre-set values, which data is worth preserving and which can be discarded. These decisions, while seemingly technical, are ultimately rooted in human biases and priorities, and they shape how meaning is transmitted and received.

These ideas were then brought to life through the analogue exercises we did in the cross year. In one, we hand-pixelated a digital image by dividing it into a grid and selecting a single colour to represent each pixel. In my case, I chose the most dominant colour in each square based on intuition and visual judgment. This act mimicked the process computers perform in milliseconds, yet doing it by hand made the process not only labour and time filled but also personal and subjective. It brought to light the fact that compression isn’t just about data loss – it’s also about decision-making and the imposition of value.

Another exercise involved translating a black-and-white photograph into a set of patterns based on the lightness or darkness of each area. We then learnt to develop a code and used a code that used those patterns to reconstruct and increasingly pixelate digital images. As more pattern-pixels were added, the image became more detailed – essentially reversing the compression logic.

These experiments helped me realise how much is lost in translation when machines make aesthetic decisions. They also highlighted a key difference between digital and human processes: time and intentionality. A computer compresses and transmits images at the speed of light, but it seems that the more time a human spends reinterpreting, compressing, and transforming data by hand, the more value it gains – because it tells a story, shows evidence of labour, and carries emotional weight.

This idea directly affects my practice, where I aim to explore the warmth and richness that come from reinterpreting digital processes through analogue, tactile methods. Rather than seeing poor-quality or compressed abstract imagery as loss of value, I am interested in reframing it as material that communicates a story – a trace of journeys through cables, screens, and human hands.

In Defense of the Poor Image

In In Defence of the Poor Image (2019), Hito Steyerl explores the aesthetics and cultural value of low-resolution digital images – what she calls “poor images.” Far from dismissing them as degraded or failed versions of their high-quality originals, Steyerl argues that these images are cultural artefacts in their own right. The “poor image” is often a by-product of repeated compression, format conversion, or unauthorised circulation. It travels through networks, is re-uploaded, copied, pirated, shared, and stripped of resolution over and over again. Yet, rather than erasing meaning, Steyerl sees this process as adding to the image’s significance. These images gain their political and social power not from clarity or sharpness, but from their accessibility, mobility, and resistance to capitalist structures of controlled distribution.

Crucially, Steyerl draws attention to the invisible labour of digital infrastructure – how images constantly travel through undersea cables, servers, and screens, compressed and decompressed by machines at rapid speed. These technical manipulations, largely automated and invisible to us, disconnect the image from its material presence and reduce its perceived value. A poor image, according to dominant cultural standards, is seen as worthless, even though its journey might have been long, charged, and deeply human.

This perspective aligns with and challenges my own practice, which focuses on translating digital data into tactile, physical forms. Steyerl’s text prompts me to ask: What if a human, not a machine, were responsible for the compression of an image? Would that repetition, that labour, add value instead of erasing it? I imagine compressing an image by hand – pixel by pixel, frame by frame – until it blurs beyond recognition. Rather than being dismissed as visual noise, such an image could become a poetic object, rich with evidence of time, attention, and craft.

In a world where data is transmitted constantly and automatically – images flowing through pulses of light across continents – there is something important about pausing to acknowledge the journey. If we knew that an image had travelled across oceans, changed hands, and been altered lovingly or laboriously (even criminally) by people, would we value it more? My practice often seeks to reintroduce this sense of presence, of human intervention, by “hacking” digital tools and repurposing them for analogue expression. I try to take on the role of the computer – not to emulate it perfectly, but to question what gets lost or preserved in translation and putting value to this.

Abstract Browsing

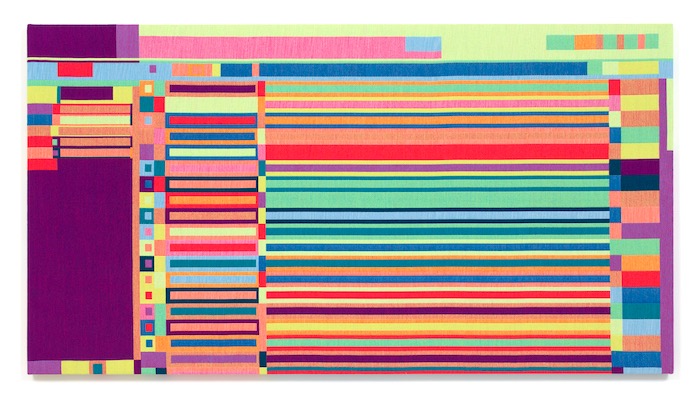

Rafaël Rozendaal’s work has been influential in shaping my understanding of abstraction and material translation. In Abstract Browsing, he created a web browser plugin that reduces online content to simple coloured rectangles, revealing the hidden architecture of websites. He then captured these compositions as screenshots and transformed a selection into woven carpets, describing weaving as a form of “mechanical painting.” This process makes the invisible structures of the web tangible and permanent.

Rozendaal defines abstraction as the removal of information – something computers do constantly. I became curious about what happens when this process is performed by hand. What if a human compresses an image? Could labour and material engagement add value instead of erasing it? His project demonstrates how filtering digital information through human decision-making – choosing what to preserve or discard – creates meaning and texture in ways algorithms cannot. Using weaving to give permanence to ephemeral visuals highlights the value of slowness, reflection, and physical presence, which resonates with my own practice: translating digital data into textiles requires intentionality, care, and labour, turning fleeting information into something sensorial and contemplative.

Rozendaal’s approach affirms my belief that abstraction can make the invisible present and render digital systems human. His framing of weaving as “mechanical painting” encourages me to consider how process, material, and perception interact, and how the act of translation – deciding what to keep, discard, or emphasise – can create meaning beyond the original data.

Fragmented Memory

Phillip David Stearns’ Fragmented Memory also aligns very well with my exploration of translating digital data into tactile, physical forms. His work challenges the idea that digital information must remain intangible, instead transforming it into woven textiles that are both materially rich and conceptually complex. This project enhances my understanding of how data can exist beyond screens and servers – how it can be embedded in a physical object and experienced through touch. Stearns’ process of converting digital glitches into textile design mirrors my own interest in taking on the computer’s logic of selecting, filtering, and encoding data, but done as a human. The tactility and physical presence of his work transforms something typically invisible and immaterial into something tangible and approachable. His work encourages me to further investigate how materiality and sensory engagement can make the digital feel less distant, changing our relationship with data as something we can touch, sense, and interpret physically.

Unraveling Stories

Unraveling Stories by Giorgia Lupi is a data visualisation-based rug design and is a powerful example of how data can be transformed into something tactile, emotional, and deeply human. In a time where digital systems dominate and traditional crafts are increasingly endangered, this project reclaims the physical and cultural significance of handmade textile processes. By weaving data about 59 disappearing textile traditions into rugs, the work not only visualises information – it honours it through form, materiality, and texture. It bridges the digital and the analogue, preserving knowledge in a format that reflects the very subject it represents. This approach aligns closely with my own practice, which explores the tension and dialogue between handmade and computer-led processes. I’m particularly interested in how we can give warmth, imperfection, and presence to otherwise cold and abstract digital information.

Adhocism

In Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation, Jencks and Silver argue that repurposing tools and materials outside their original intent can be a valid and creative strategy rather than simply a workaround. This idea resonates strongly with my area of interest, where I explore the interplay between analogue and digital. Their concept of “hacking” a medium supports my approach of misusing or bending tools to uncover new possibilities – questioning not just how something works, but why it must work in a particular way. Rather than aiming for precision or digital perfection, I intentionally embrace imperfection and intuition to make decisions usually reserved for the machine. Adhocism enhances my understanding of experimentation as not only acceptable, but necessary when challenging systems built on speed, compression, and invisibility. It encourages me to value manual labour and unpredictability in contrast to automated efficiency, and it frames limitations as a powerful space for creativity. This perspective helps validate my ongoing investigations into physicalising intangible data by using analogue processes in unfamiliar, open-ended ways.

The Medium is the Massage

McLuhan and Fiore’s The Medium is the Massage deepens my understanding of how media shape not only the message, but also the way we perceive and engage with information. Their idea that “the medium is the message” aligns with my practice. By stepping into the computer’s role, deciding what data to preserve or discard, I highlight the human hand and the imperfections that come with it. The book’s fragmented, rhythmic layout mirrors this interest in translation and disruption. It uses sequencing, repetition and contrast to guide the reader’s experience, not just through content but through form. This reinforces my belief that the material and sensory qualities of a medium are not secondary bur rather they are the message. Working against the expected function of a tool or process, such as using textiles to convey digital data, allows me to ask what new meanings emerge when the invisible medium is made visible. McLuhan and Fiore help me consider not only what I’m communicating, but how the method of communication transforms the message itself.

Generative Knitting, Olivia Glennon

This project explores the intersection of data, code, and textile-making by translating photographic information into knit patterns using a hacked 1990s electronic knitting machine. Drawing inspiration from the Jacquard loom and artists like Claire Williams and Anni Albers, the team developed custom software to extract colour palettes from images and map them onto digital knitting blueprints. These patterns were then physically produced with a hacked knitting machine, with the project embracing both the limitations and unexpected outcomes of the medium. The process highlights a curiosity for how digital systems can be reimagined through tactile, imperfect, and materially grounded practices.

This approach closely aligns with my own area of interest: translating digital data into physical forms by “hacking” or repurposing tools in ways they weren’t originally designed for. I’m particularly interested in how this project frames the act of knitting not only as craft but as computation – highlighting the labour, error, and decision-making that challenges digital perfection. It reinforces my project’s belief that analogue processes can offer rich alternatives to screen-based interaction, allowing information to be felt and experienced in ways that are more human, intimate, and materially nuanced.

Irene Albino – </unravel;>

The project </unravel;> by Ellen Jonsson and Irene Albino strongly resonates with my interest in the intersection of digital systems and physical craft. By knitting a 25-metre-long essay over several days, they merge analogue and digital processes in a way that challenges the conventional divide between the two. Their method of encoding text – traditionally understood as digital data – into knitted form reframes communication as something slow, tangible, and the content of the text is rooted in feminist craft traditions.

The artists hacked an 1980s Brother knitting machine, a hybrid analogue-digital device that can be programmed via connection to an old IBM computer. They then linked this system to a modern computer, such as a MacBook, and developed code to interpret BITMAP images, translating pixels into stitches. In this case, the images were their written text, knitted as a performative piece that exposed patterns through hidden messages – text to image to pixel to pattern.

This work has deepened my understanding of how tactile translation can critically engage with digital culture. It demonstrates that coding, often perceived as abstract and disembodied, can be embedded in material processes with cultural and historical significance. The project’s focus on audience interaction and reflection highlights how physical engagement with data can generate embodied experiences and contemplative spaces—an approach I aim to explore in my own practice. Jonsson and Albino reclaim knitting not as a hobby, but as a medium for critical storytelling, showing how physicalising data can also embody values, identities, and cultural critique.

Positions Through Triangulating

My project

My project explores the relationship between digital systems and textile making through the lens of error. By translating binary code into knitted form and observing how mistakes appear and unfold, I investigate how imperfection exposes the hidden structures underpinning both computing and craft. I see the glitch or accident not as a flaw but as a moment of revelation – a way of making digital systems human, tangible, and fragile. Through this process, I explore how breakdowns and mistakes become tools for understanding and reimagining systems.

Error reveals the system

By converting the alphabet into ASCII binary code and reinterpreting this system as a pixelated structure, I created a diagram similar to how knitting patterns are usually displayed. Using this diagram, I produced a knitted piece, exploring the connection between digital logic and tactile logic through the translation of words into knitted code.

Anni Albers – On Weaving

Anni Albers’s On Weaving (1965) offers a position in productive tension with mine. Written by one of the twentieth century’s most influential textile artists, the book remains central to understanding the intersection of craft, design, and thought. Albers mixes technical description with aesthetic reflection, explaining the mechanics of weaving – warp, weft, loom, drafts, constructions – while framing weaving as a structural, problem-solving activity with aesthetic consequences. On Weaving is not a manual but a study of textile thinking as design philosophy: how constraint and material structure shape creative ideas.

While Albers argues for weaving as disciplined problem-solving, my project deliberately creates problems. I am interested in how things fall apart – how mistakes or fragility reveal systems that otherwise remain invisible.

Structure as Order vs. Structure as Exposure

In On Weaving, Albers celebrates the loom as a rational system that generates clarity through its constraints. For her, beauty emerges from discipline. The weaver’s task is to understand the rules and use limitations as a framework for invention. She describes weaving as “an event of a thread,” a negotiation between material, technique, and idea. Harmony arises when every element – warp, weft, fibre, tension – is balanced and controlled.

My project stands on the other side of that harmony. Where Albers seeks to master the system, I let it unravel. By introducing glitches, I move from order to instability. For me, structure is not a way to clarity but a field where collapse is always possible. Both of us share a fascination with systems and their logic, but where Albers sustains beauty through control, I expose it through disruption. This contrast raises a question: must revelation always come through failure? Albers finds meaning in control, in the intelligence of a well-resolved problem. My work suggests that understanding can also arise from breakdown – that knowledge might live in those loose threads where control is lost.

Back-End vs. Front-End

The “front” of my knitted work represents the perfect system: the readable pattern, the intended outcome. Yet the reverse side reveals another kind of information. Behind every neat surface lies a web of crossovers, yarn ends, and knots. In digital systems, the same is true – a polished interface conceals the complexity of its back-end code. Comparing the wrong side of knitting to a computer’s back-end reveals how visibility shapes understanding: the front hides the system; the back exposes it.

This double-sidedness mirrors two modes of making: Albers’s structural clarity vs my deliberate entanglement and detanglement. For her, the goal is to make the structure seamless. For me, it is to make it seen. A dropped stitch that unravels an entire piece is the textile equivalent of a coding error that crashes a program. Both show the interdependence of systems – how a tiny mistake ripples outward to create greater consequences.

Systems

Despite our slightly different approaches, Albers and I share a belief that textiles embody systems of logic – processes built on repetition, interdependence, and transformation. Her emphasis on problem-solving mirrors computer code: a structured sequence of instructions. In that sense, her weaving anticipates the logic of computing. My work extends this by merging the two systems – translating digital code into knitted form.

Weaving, knitting, and coding are parallel forms of thinking. Each transforms a linear sequence – a thread / a line of code – into structure, containing both order and disorder. Albers’s vision of structure as clarity and mine of structure as exposure may simply be two sides of the same system – like the two sides of a knit.

Just Tie Knots

The craft movement in Denmark shifted from the older ethic of craft where control and precision was valued, to Lærke Bagger’s “Just Tie Knots” philosophy which celebrates imperfection and reflects a shift: flaws are now valued as traces of the maker’s hand, as proof of authenticity and process.

This movement resonates with my embrace of the glitch. In digital systems, errors signal human presence – the moment when code fails to suppress the material. In textiles, mistakes expose labour and fragility. By aligning the digital glitch with the handmade mistake, I dissolve the boundary between algorithmic and tactile thinking. Both reveal their systems through imperfection.

Shifting from Digital to Tactile

Working between textiles and digital media means navigating changes of medium, scale, and speed. A line of binary code, when knitted, becomes slow and physical. A digital glitch happens in milliseconds; a dropped stitch unfolds over time, visible to the hand. Computers process errors instantly and invisibly; knitters must confront them, repair them, or let them grow.

Conclusion

Through studying On Weaving, I have come to see my project as a conversation with Albers rather than an opposition. Her insistence on structure, control, and material intelligence challenges my fascination with the glitch. It asks whether disorder alone can produce understanding, or whether discipline also holds revelation.

Perhaps, as both weaving and computing suggest, systems only truly reveal themselves in the balance between order and collapse – between what holds together and what comes undone. In this sense, my work continues the thread Albers began, but from the other side of the weave. Where she constructs harmony through structure, I expose the fragility beneath it. Both positions share a respect for the system – one seeking its perfection, the other tracing its faults. Together, they weave a dialogue between control and chance, hand and code, intention and error.

Positions Through Dialogue

Dialogue with Irene Albino

I had the opportunity to speak with Irene Albino, and our conversation was an important point of reflection for my practice. As my enquiry developed to focusing on a digital glitch in a tactile environment, my conversation with Albino prompted me to ask myself questions:

What causes the glitch?

Why does it happen?

What is the method or mechanism behind it?

Is the glitch related to time, translation, space, or the transformation of image, text?

Albino noted that she had not encountered the concept of a glitch in relation to national identity or cultural background before. We also discussed my research into traditional knitted sailor patterns, where information on definitions and meanings is scarce. She suggested that this absence is productive—it creates a space for me to intervene and uncover new meanings. In my project, the shift in identity or the shift in time itself can act as a conceptual glitch, linking digital experimentation with the histories and traditions embedded in textile systems.

Synthesis

Knitted Sailor Sweaters and Scandinavian Patterns

Historically, sailor sweaters were hand-knitted with a clear purpose: to keep fishermen warm while out at sea. Beyond their practical function, these sweaters also communicated identity through pattern. Each design was personal, often indicating the wearer’s village or family. When fishermen returned from dangerous journeys, their families could recognise them by these patterns, signalling that their loved ones had come home safely (DR, 2022).

Today, however, this sense of identity has largely disappeared. Most knitted sweaters are now machine-made and sold through fast fashion chains. Thousands of people wear identical garments, and the personal meaning once embedded in each pattern has been lost.

The value of the handmade

The value of the handmade remains clear. When someone compliments a hand-knitted sweater, the response is far more enthusiastic than if it came from a commercial brand such as Zara or H&M. This reaction reflects the time, care, and skill involved in creating a unique piece. In hand knitting, while multiple people may follow the same knitting pattern, the inevitable variations in hand tension, fibre, and small mistakes ensure that no two sweaters are truly identical. These subtle differences – slight variations in stitch, texture, and colour – make each handmade sweater singular, carrying a trace of the maker’s hand and identity.

Analogue vs Digital – Glitch

Using the idea of a system, such as a knitting pattern, we can draw parallels to computers. When different computers follow the same set of systems and instructions, they produce identical results. This led me to explore the interplay between digital and analogue processes – how mediums and outcomes interact and transform each other, both conceptually and practically.

I turned my focus to the digital and to something typically seen as existing only in that realm: the glitch. A glitch can be described as a temporary, minor malfunction or irregularity, manifesting as visual distortions, sudden interruptions, or other unintended behaviors. Defined simply, a glitch is “a small problem or fault that prevents something from being successful or working as well as it should” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.).

I wanted to expand on this definition. While a glitch is traditionally associated with failure, the beauty and value of the handmade often lies precisely in its mistakes – its irregularities and imperfections. This inspired me to investigate how a glitch could be reimagined as something generative, adding value, and whether it could be understood through the analogue eye, through the hand.

Enquiry

What if we could take the error of a machine and make it human, personal, and

tactile?

Could a digital glitch be used to “hack” a system and give it qualities similar to

something handmade?

For my project, I experimented with traditional Scandinavian knitting patterns, deliberately incorporating computer-generated errors into the system. Each pattern produced became unique, echoing the individuality of hand-knitted sweaters, where no two outcomes are ever identical.

Conceptually, the glitch also reflects a shift in time and tradition. Through digitalisation, industrialisation, and fast fashion, the practice of hand-making has increasingly been replaced by machines. By embracing these glitches, my project highlights both a literal error and a conceptual one – a commentary on how tradition, craft, and identity are affected by contemporary processes.

Ultimately, these deliberate irregularities celebrate the value of the handmade: each piece becomes one-of-a-kind, capable of representing different identities, while bridging the analogue and digital, the human and the computational.

Reference list

Albers, A. (1965) On Weaving. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Bagger, L. (2021) Strik. Copenhagen: Gyldendal Nordisk Forlag. ISBN 978-8702316353.

Cambridge Dictionary (2025) glitch. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/glitch (Accessed: 10 November 2025).

Carr, E. (2021) Tycho Jones – “Don’t Be Afraid” [music video]. 12 May 2021. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MqIAbnSQuN4 (Accessed: 10 November 2025).

DR (2022) Færøerne – Kaos på fjeldet, TV episode, 22 October. Available at: https://www.dr.dk/drtv/episode/færøerne-kaos-på-fjeldet (Accessed: 10 November 2025).

Glennon, O. (2019) Generative knitting, Medium.

Jencks, C. and Silver, N. (2013) Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation. [1972] Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp.38–53.

Jonsson, E. and Albino, I. (2018) < /unravel; >. [textile installation] Central Saint Martins Degree Show, London.

Lupi, G. (n.d.) Unraveling Stories. [textile collection] Pentagram and Well Woven.

McLuhan, M. and Fiore, Q. (2001) The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. [1967] Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press.

Rozendaal, R. (n.d.) Abstract Browsing. [software project and textile series]

Stearns, P.D. (2013) Fragmented Memory. [textile triptych] Tilburg: Audax Textielmuseum’s Textiellab.

Steyerl, H. (2019) In defence of the poor image.

Wikipedia (2025) Jacquard machine. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jacquard_machine (Accessed: 10 November 2025).

Wikipedia (2025) Luddite. Available at: https://www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite (Accessed: 10 November 2025).