Methods of contextualising

Re-imagining exhibitions

A joyful experience

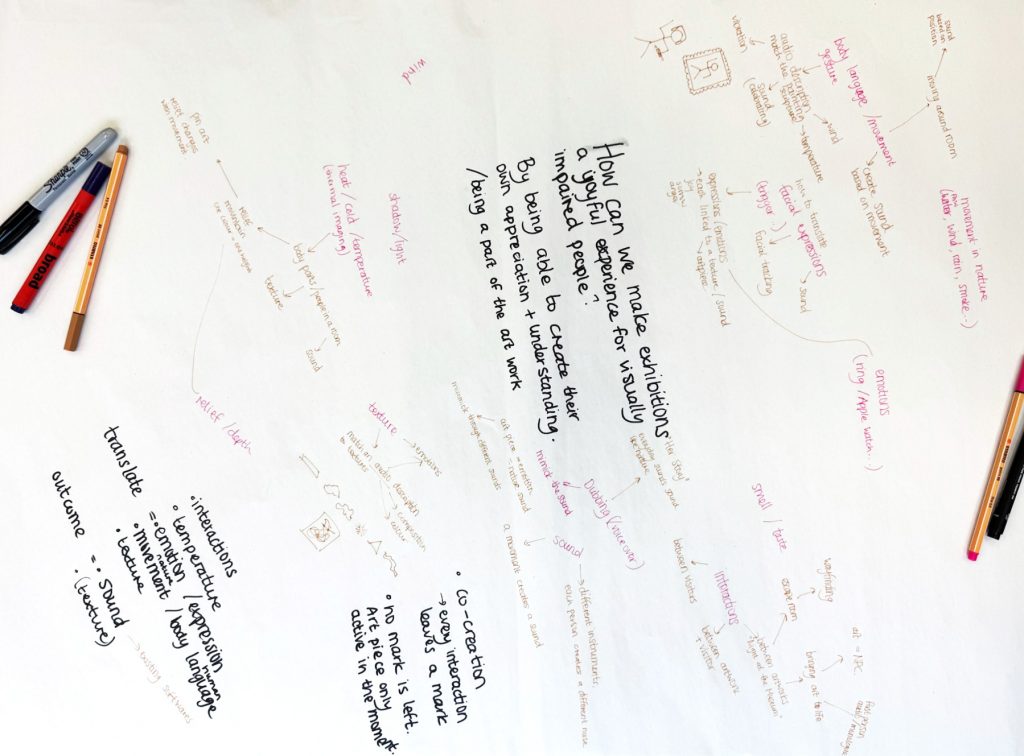

For this group project, we started off by brainstorming and identifying places of joy

Joyful experiences we had in common were exhibitions and restaurants. We brainstormed the barriers that could be experiences to people with disabilities.

We decided to continue with exhibition as our place and we decided that our target group were people with visual impairment. Visual impairment (according to “Identifying Barriers to Accessibility for Museum Visitors Who Are Blind and Visually Impaired“) can be categorised into three – low vision, legal blindness and total blindness. We chose to focus on people with total blindness to completely remove vision as a sensory method.

site visit to v&a

At our site visit to the V&A museum, it was clear that it wasn’t very accessible to people with total blindness. Only one section of the museum had an audio guide, the vast majority of paintings and sculptures were accompanied by a “do not touch” sign. A few pieces had braille explanations and a few had audio descriptions.

nothing about us without us

An important references for this projects was “Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need” that highlights the principle “Nothing About Us Without Us,” advocating for inclusive, community-led design. It reminded us that to design for people with visual impairment, it is important to include them in the design process and developing.

Identifying Barriers to Accessibility for Museum Visitors Who Are Blind and Visually Impaired

This is a study which gathered feedback on accessibility from 12 people with visual impairment to inform a major renovation at the Grand Rapids Public Museum in the US. Because of the time limit of this project, we did not have the opportunity to directly involve anyone with legal blindness and therefore we used this study to guide our process.

How can we re-imagine exhibitions pieces through sound and touch to create interaction and individual understanding of the art pieces and make the experience more joyful for people with total blindness?

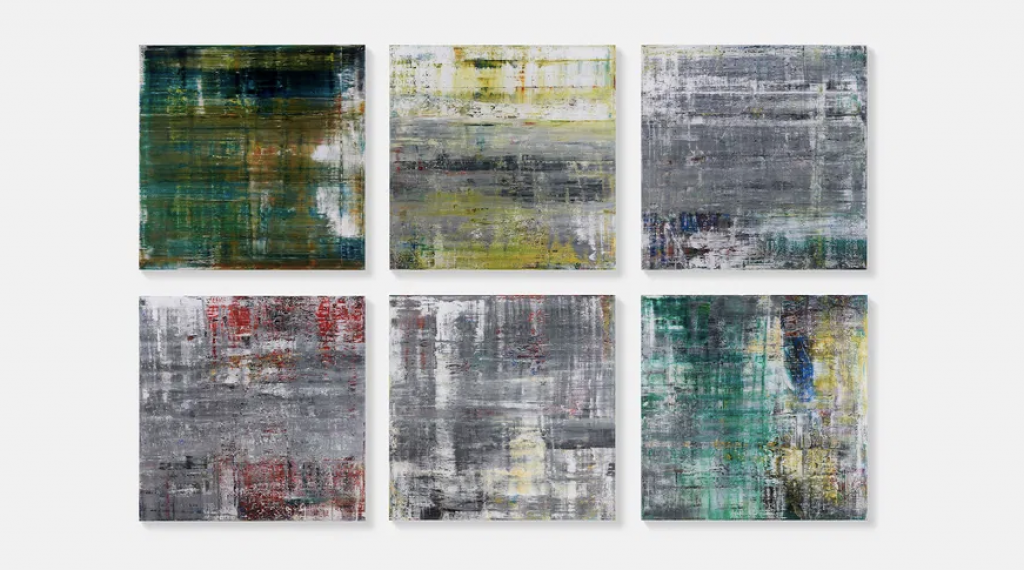

Gerhard Richer’s “Cage 1-6”

We did a site visit to the Tate Modern, where we came across these 6 big paintings by Gerhard Richer. These paintings were created whilst listening to music by John Cage, inspired by Cage’s ideas about ambient sound and silence and his controlled use of randomness. Richer layers his paint and creates his artwork through the use of pauses, brushstrokes and scrapings.

We chose to pick these paintings to re-imagine based on their visual features such as colour, composition, darkness/brightness, brushstrokes and texture.

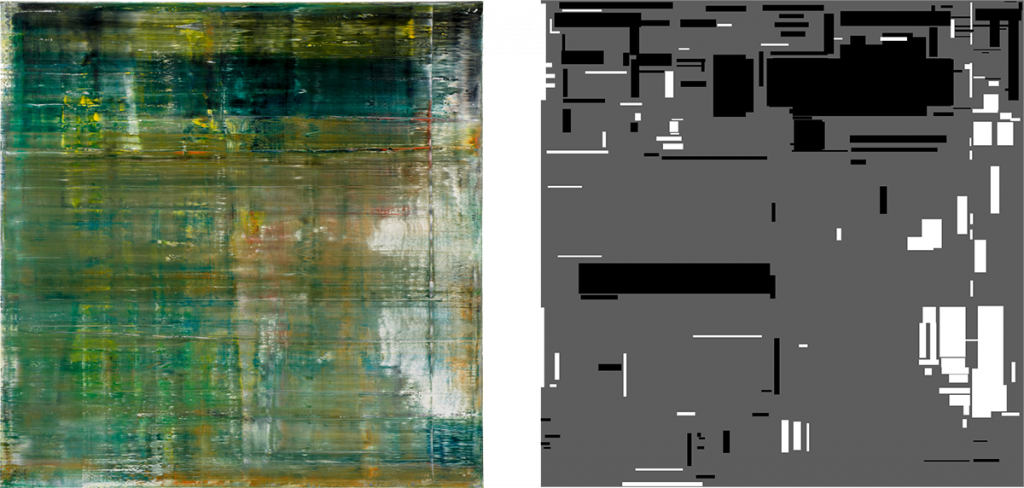

Darkness & brightness

I translated the darkness and brightness of “Cage 1” by re-imagining it as visual blocks.

Focusing on the darkness blocks, I translated these into sound by drawing them into notes on a keyboard using Garage Band.

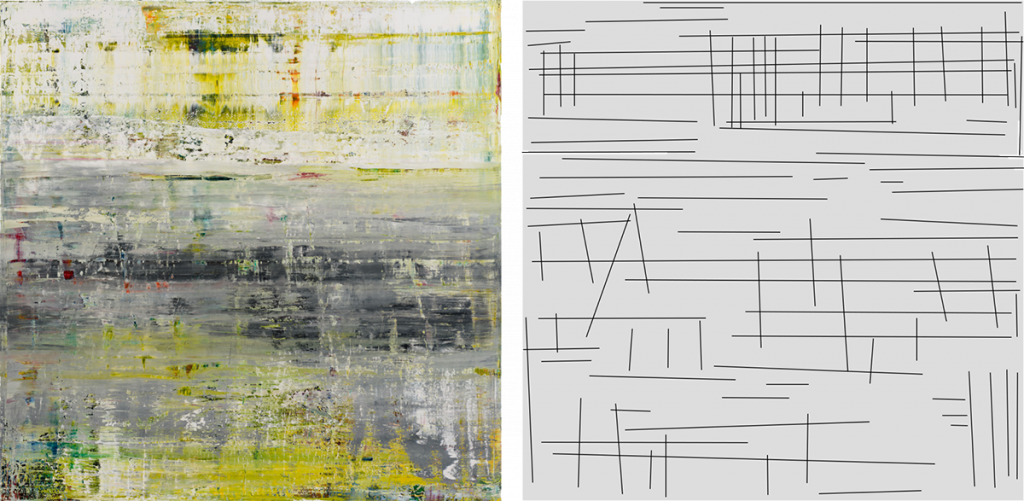

brushstrokes

I translated the directions of the brushstrokes into lines and translating these horizontal lines into sound using piano keys.

Brushstrokes to texture

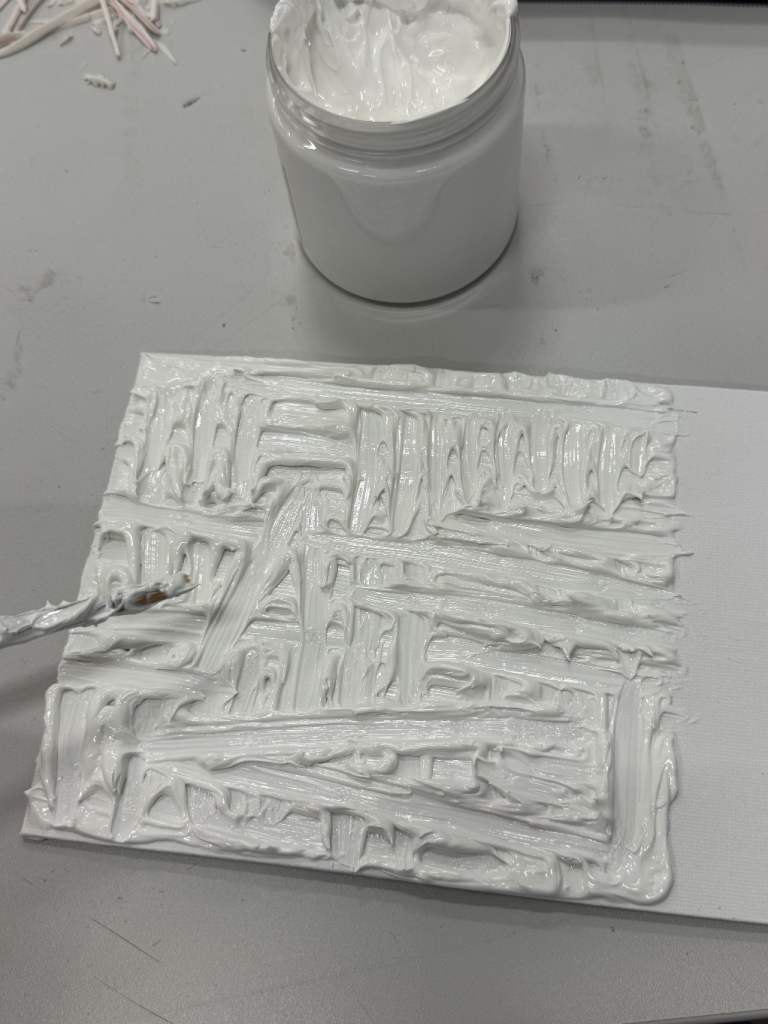

I then translated the brushstroke directions into relief and texture by using Lino cutting and modelling paste

Colour to Sound

In Concerning the Spiritual in Art, Kandinsky explores the relationship between colour, form and sound, and suggests that different colours resonate with different musical instruments

Red – trumpet

Blue – clarinet

White – piano

Yellow – xylophone

Green – violin

Black – contrabass

Brushstrokes to sound

We translated the brushstrokes into everyday sounds that we thought corresponded well

Flat brushstroke – wind blowing

Dry brush – sweeping leaves

Overlay – water dripping

Scrape – knife on toasted bread

We used Kandinsky’s theory and converted the colours of “Cage 6” into the sounds of these instruments and combined it with the “sound” of the brushstrokes.

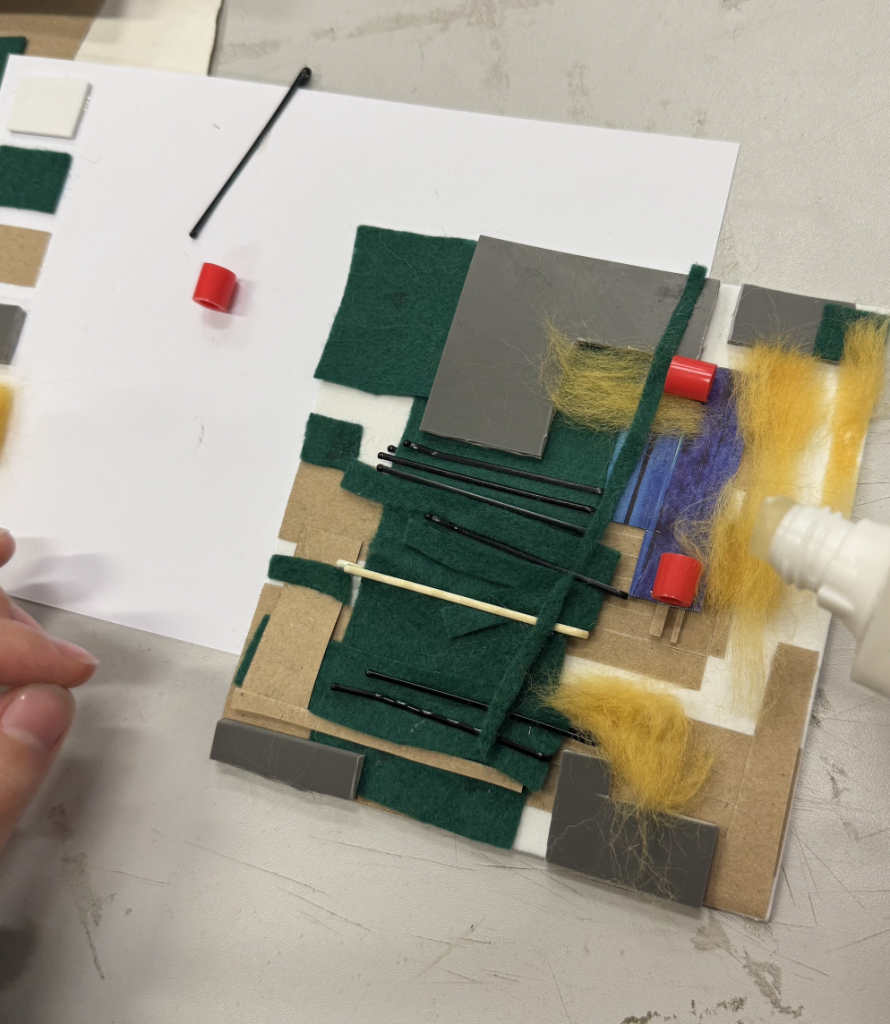

COlour to touch

We used different materials to each represent a colour and translated “Cage 6” into texture

Collection outcome

Three interactive ways of interpreting paintings through touch and sound

Written response

My position as a practitioner in context of Disability Justice

Exploring this project has deepened my understanding of Disability Justice, particularly in relation to visual impairment. It made me aware of how much of our world assumes sightedness, something I (and I’m sure also the majority of sighted people) take for granted every day. As a very visual person, I interpret and express myself through visuals, but this exploration challenged me to engage with the world beyond what is seen through the eyes.

The vast majority of things in our everyday lives – the things we encounter, the things we experience, and the things that are explained to us – are all driven by the assumption that we can all see the same thing. This project has highlighted for me the beauty of not understanding things in the same way. Sound and touch are subjective; when described, there is no single, universal interpretation. In contrast, visual communication tends to be described more objectively, as sighted individuals often assume a shared understanding of what they see. This realisation has made me question how we communicate and interpret experiences. If visuals were described in more abstract terms rather than objectively, and if senses such as hearing and touch were prioritised, it would not only create inclusivity for those with visual impairments but also enrich experiences for sighted individuals to think more creatively and deeply about what they see and form their own meanings.

Annotated Bibliography

From the course reading list

Bolt, B. (2021). Beneficence and contemporary art: When aesthetic judgment meets ethical judgment. In: The Meeting of Aesthetics and Ethics in the Academy: Challenges for Creative Practice Researchers in Higher Education, pp. 153–166.

Bolt explores how ethical considerations influence contemporary artistic practice, challenging the separation between artistic freedom and moral responsibility. She argues that artists, educators, and institutions must consider the ethical implications of their work, ensuring that art contributes positively to society rather than merely provoking reactions. She discusses the term “beneficence”, the ethical obligation to do good, which highlights the responsibility of artists to engage critically with their practice.

This reference deepened my understanding of accessibility in exhibitions, shifting my focus from simple technical adaptations to a more inclusive, participatory approach. It encouraged us as a group to rethink accessibility as an integrated experience rather than a separate accommodation. Often, accessibility in exhibitions isolates visually impaired audiences with separate descriptions, audio guides, or braille text. Instead, we explored how all visitors – sighted or visually impaired – could engage with art in the same way, using sound and touch. This aligns with Bolt’s ethical perspective, ensuring that accessibility is not just about inclusion but about enabling multiple interpretations.

McLuhan, M. & Fiore, Q. (1967) The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. Berkeley: Gingko Press.

McLuhan argues that media do more than passively convey content – they actively shape how we perceive and engage with the world. He highlights that changing a medium is not just about transferring information but about reconstructing meaning. A painting viewed with the eyes offers a completely different experience than one interpreted through sound or touch. This idea has been fundamental to our process, as it shifts the focus from accessibility alone to rethinking how art can be experienced, making us reflect on the purpose and objectives of this project.

Rather than replicating the original paintings for visually impaired audiences, our project seeks to create an alternative form of engagement. Conventional accessibility tools like audio descriptions and braille often impose a predetermined understanding of an artwork, whereas our approach encourages open-ended interpretation. If the medium shapes perception, then transforming a painting into sound and touch inevitably alters its meaning. Are we providing access to the original, or are we creating an entirely new experience? This question has driven our exploration, challenging us to consider whether our project enhances accessibility or redefines the artwork itself.

Outside the course reading list

Costanza-Chock, S. (2020). Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. MIT Press.

This text highlights the principle “Nothing About Us Without Us,” advocating for inclusive, community-led design. It challenges traditional design approaches that often exclude marginalised voices, arguing that those directly affected by design decisions should lead the process. The book promotes equality, accessibility, and co-creation, ensuring that design serves collective well-being rather than reinforcing injustices.

As seen through our project, having this reference to keep referring back to was a good reminder not to assume anything about the needs of people with visual impairment and that creating “for them” should rather be approached as “creating with them/alongside them.” If we had a longer timeframe for this project, we would have developed our project alongside people with visual impairment and run multiple tests to create a space for feedback and continual improvement.

As described in the reference, instead of aiming for a single “universal” experience, design should offer flexible solutions, such as customisable sensory settings and multiple ways of engagement. This approach enhanced our project by not focusing on one specific solution but rather a set of solutions to enhance experiences for those with visual impairment. We explored touch and sound as ways to experience art, experimenting with different methods to translate visuals into sound, as well as using different types of relief and texture as ways to interpret and communicate information through touch.

Bourriaud, N. (1998). Relational Aesthetics. Les Presses du Réel.

In Relational Aesthetics, Nicolas Bourriaud explores contemporary art that prioritises human interaction and social engagement over traditional aesthetic concerns. He argues that art is no longer confined to objects but exists in the relationships it fosters between people. Bourriaud describes how artists create participatory experiences, turning exhibitions into spaces for dialogue and collaboration. This shift challenges conventional ideas of authorship and spectatorship, positioning the audience as an active participant rather than a passive observer.

This vision has influenced our project and made us critically question the overall purpose of art in exhibition spaces. Rather than viewing art as something purely visual or aesthetically pleasing, we explored its potential to create interactions between people and engage audiences beyond passive and visual observation. Bourriaud’s ideas challenged us to consider whether art should be a shared experience rather than an individual one and whether its true value lies in the participation and interaction. Experimenting with multi-sensory approaches ensures that art can be experienced differently by everyone, rather than relying on a singular, fixed interpretation and sense.

Design practices and projects

Flying Object. (2015). Tate Sensorium: An Experiment in Multi-Sensory Art Viewing. Tate Britain.

Tate Sensorium was a multisensory exhibition at Tate Britain, designed by Flying Object for the IK Prize 2015. It enhanced the experience of four paintings using sound, touch, scent, and taste, challenging the dominance of sight in traditional galleries. Visitors engaged with custom soundscapes, textures, scents, and flavored chocolates inspired by the artworks. Biometric sensors tracked responses, exploring how multisensory engagement deepens perception. The project redefined art accessibility, making exhibitions more immersive and inclusive, particularly for visually impaired audiences.

The way Tate Sensorium questioned traditional art experiences and highlighted the potential of multisensory design in making art more inclusive closely aligns with our project’s approach. The exhibition’s popularity and recognition indicate that such experiences are not commonly explored, despite strong public interest. Looking at this reference, we considered how their sensory elements were developed in collaboration with sound designers, to reflect the atmosphere, themes, and historical context of each painting. However, in our project, we deliberately took a more abstract approach. Our sounds were generated by translating visual features like brushstrokes and colours, to not predetermine any assumptions of the art pieces. This allows participants to form their own meanings, leading to a more open-ended and personal experience of the artwork.

DX Lab, State Library of New South Wales (2018) 80Hz.

Available at: https://dxlab.sl.nsw.gov.au/80hz/

80Hz was an interactive pavilion at the State Library of NSW, where AI translated paintings into unique sound compositions. Developed by DX Lab, the project used machine learning to analyse visual elements such as colour, contrast, date, artist, and brushstroke movement and map them to different musical instruments, rhythms, and tones. Visitors could listen to how each painting “sounded,” offering a new, sensory way to experience visual art. The project explored the intersection of art, technology, and perception, challenging traditional ways of engaging with paintings.

The sounds created in 80Hz are musically composed and structured, making them feel more polished and intentional. When listening, I naturally associate the sounds with specific emotions, places, or colours, which highlights the project’s ability to guide perception. However, in our project, we deliberately took a different approach by creating messy, layered, and “wrong-sounding” compositions that shouldn’t create immediate associations. We purposely avoided researching how the paintings were traditionally interpreted, ensuring that each listener has the space to construct their own meaning from the experience, even if it’s completely different to the one originally intended. While this approach may be very abstract, it reinforces our project’s belief that art should be unrestricted and shaped by individual perception rather than predefined interpretations.