How can I visually communicate the unseen and translate something purely digital to tactile?

How can I replicate/humanise what the computer does?

How can I preserve data that exists online?

Written response

My area of interest

I explore the interplay between analogue and digital by translating data into tactile, physical forms. Taking on the computer’s role, I decide what to preserve or discard and reintroduce human warmth and imperfection to otherwise intangible information. My practice often involves “hacking” tools and mediums – using them in unintended ways to challenge their original purpose and uncover new possibilities.

annotated bibliography

Fragmented Memory

Stearns, P.D., 2013. Fragmented Memory. [textile triptych] Tilburg: Audax Textielmuseum’s Textiellab.

Phillip David Stearns’ Fragmented Memory aligns very well with my exploration of translating digital data into tactile, physical forms. His work challenges the idea that digital information must remain intangible, instead transforming it into woven textiles that are both materially rich and conceptually complex. This project enhances my understanding of how data can exist beyond screens and servers – how it can be embedded in a physical object and experienced through touch. Stearns’ process of converting digital glitches into textile design mirrors my own interest in taking on the computer’s logic of selecting, filtering, and encoding data, but done as a human. The tactility and physical presence of his work transforms something typically invisible and immaterial into something tangible and approachable. His work encourages me to further investigate how materiality and sensory engagement can make the digital feel less distant, changing our relationship with data as something we can touch, sense, and interpret physically.

Jacquard Loom

Wikipedia (2024). Jacquard loom. [online]

The Jacquard loom is a machine that exemplifies the deep historical link between data and textile. Its use of punch cards to control woven patterns marked a fundamental shift in how information could be stored, manipulated, and materialised – an early coming together of the digital and the physical. This adds strong history to my interest in using analogue tools to reinterpret digital systems. Just as the Jacquard loom was one of the first machines to encode data into fabric, I want to explore how data can be made tangible through craft, while questioning and hacking the original function of tools. The Jacquard loom, often cited as a precursor to modern computing, helps frame weaving not simply as a decorative act, but as a form of code, memory, and computation – adding historical and conceptual depth to my own approach.Abstract Browsing

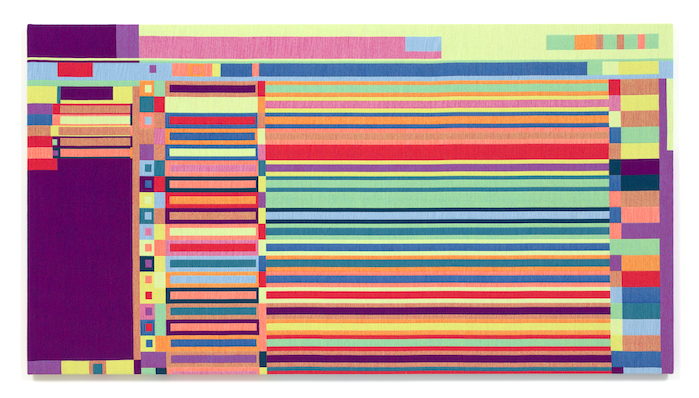

Rozendaal, R., n.d. Abstract Browsing. [software project and textile series]

Abstract Browsing

Rozendaal, R., n.d. Abstract Browsing. [software project and textile series]

Rafaël Rozendaal’s Abstract Browsing enhances my understanding of how digital structures can be reframed through material translation. In this project, Rozendaal developed a web browser plugin that reduces all online content to abstract coloured rectangles, revealing the hidden architecture of websites. He then captured compositions as screenshots and transformed a curated selection into woven carpets – describing the process of weaving as a form of “mechanical painting.” This distillation of digital content into abstract form is relevant to my own practice of translating intangible data into tactile, physical outputs. Like Rozendaal, I am interested in filtering digital information through human decision-making, deciding what to preserve and what to discard. His use of weaving to give permanence and texture to momentary screen-based visuals reinforces the value of slowness, reflection, and physical presence in a fast-paced, immaterial digital world full of procrastination and distractions. Abstract Browsing encourages me to consider how materialising data not only reshapes its meaning but also creates space for sensory engagement and contemplation. He describes abstraction as removal of information which is what the computer is always doing. It affirms my belief that abstraction can serve as a powerful tool for making the invisible feel present, and the digital feel human.

“I’ve tried to spend less time on the computer

turning procrastination into productivity

finding beauty in utility

abstraction => removal of information

from natural perception to material reduction

distraction based compositions

infinite information – infinite compositions

the aesthetics of distraction

abstraction is an escape

appropriated abstraction

weaving => mechanical painting”

Unraveling Stories

Lupi, G., n.d. Unraveling Stories. [textile collection] Pentagram and Well Woven.

Unraveling Stories by Giorgia Lupi is a data visualisation-based rug design and is a powerful example of how data can be transformed into something tactile, emotional, and deeply human. In a time where digital systems dominate and traditional crafts are increasingly endangered, this project reclaims the physical and cultural significance of handmade textile processes. By weaving data about 59 disappearing textile traditions into rugs, the work not only visualises information – it honours it through form, materiality, and texture. It bridges the digital and the analogue, preserving knowledge in a format that reflects the very subject it represents. This approach aligns closely with my own practice, which explores the tension and dialogue between handmade and computer-led processes. I’m particularly interested in how we can give warmth, imperfection, and presence to otherwise cold and abstract digital information.

</unravel;>

Jonsson, E. and Albino, I., 2018. < /unravel; >. [textile installation] Central Saint Martins Degree Show, London.

The project < /unravel; > by Ellen Jonsson and Irene Albino resonates with my interest in exploring the intersection of digital systems and physical craft. By knitting a 25-metre-long essay over a couple of days, they blend analogue and digital in a way that challenges the divide between the two. Their approach to encoding text – traditionally seen as digital data – into knitted form reframes digital communication as something slow, tangible, and rooted in feminist craft traditions.

This work enhances my understanding of how tactile translation can critique digital culture. It shows that coding, often seen as disembodied and abstract, can instead be embedded in material processes with cultural and historical focus. The project’s emphasis on audience interaction and reflection reinforces the idea that physical engagement with data and information can create deeper, more embodied experiences and space for contemplation – something I want to explore in my own practice. Jonsson and Albino reclaim knitting not as a hobby but as a medium for critical storytelling and helps me see how physicalising data can also physicalise values, identities, and cultural critique.

Adhocism

Jencks, C. and Silver, N., 2013. Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation. [1972] Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp.38–53

In Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation, Jencks and Silver argue that repurposing tools and materials outside their original intent can be a valid and creative strategy rather than simply a workaround. This idea resonates strongly with my area of interest, where I explore the interplay between analogue and digital by translating data into tactile, physical forms. Their concept of “hacking” a medium supports my approach of misusing or bending tools to uncover new possibilities – questioning not just how something works, but why it must work in a particular way. Rather than aiming for precision or digital perfection, I intentionally embrace imperfection and intuition to make decisions usually reserved for the machine. Adhocism enhances my understanding of experimentation as not only acceptable, but necessary when challenging systems built on speed, compression, and invisibility. It encourages me to value manual labour and unpredictability in contrast to automated efficiency, and it frames limitations as a powerful space for creativity. This perspective helps validate my ongoing investigations into physicalising intangible data by using analogue processes in unfamiliar, open-ended ways.

The Medium is the Massage

McLuhan, M. and Fiore, Q., 2001. The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects. [1967] Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press

McLuhan and Fiore’s The Medium is the Massage deepens my understanding of how media shape not only the message, but also the way we perceive and engage with information. Their idea that “the medium is the message” aligns with my practice, where I translate digital data into tactile, physical forms to explore what gets lost or transformed in that process. By stepping into the computer’s role, deciding what data to preserve or discard, I highlight the human hand and the imperfections that come with it. The book’s fragmented, rhythmic layout mirrors this interest in translation and disruption. It uses sequencing, repetition and contrast to guide the reader’s experience, not just through content but through form. This reinforces my belief that the material and sensory qualities of a medium are not secondary bur rather they are the message. Working against the expected function of a tool or process, such as using textiles to convey digital data, allows me to ask what new meanings emerge when the invisible medium is made visible. McLuhan and Fiore help me consider not only what I’m communicating, but how the method of communication transforms the message itself.

Edd carr, Don’t Be Afraid by Tycho Jones (music video)

Edd Carr’s cyanotype-based animation resonates with my interest in using a medium in a way it is not intended and also going back and forth between translating digital information to analogue material outcomes. His process – shooting a video and then printing each video frame as a cyanotype and digitally reassembling them into moving image – acts as a way to use handmade techniques to slow down and disrupt digital motion. What fascinates me is how Carr embraces the inherent slowness, unpredictability, and imperfections of cyanotype as integral to the work’s aesthetic and meaning, rather than seeing them as limitations. His method effectively “hacks” both the medium and the animation process, challenging assumptions that movement and data belong exclusively to the digital space. While my own practice currently focuses on keeping the final outcomes analogue, Carr’s work reinforces how analogue techniques can carry, translate, and even enhance digital content – embedding it with human presence and physicality/tactility.

Gente Ampli2*

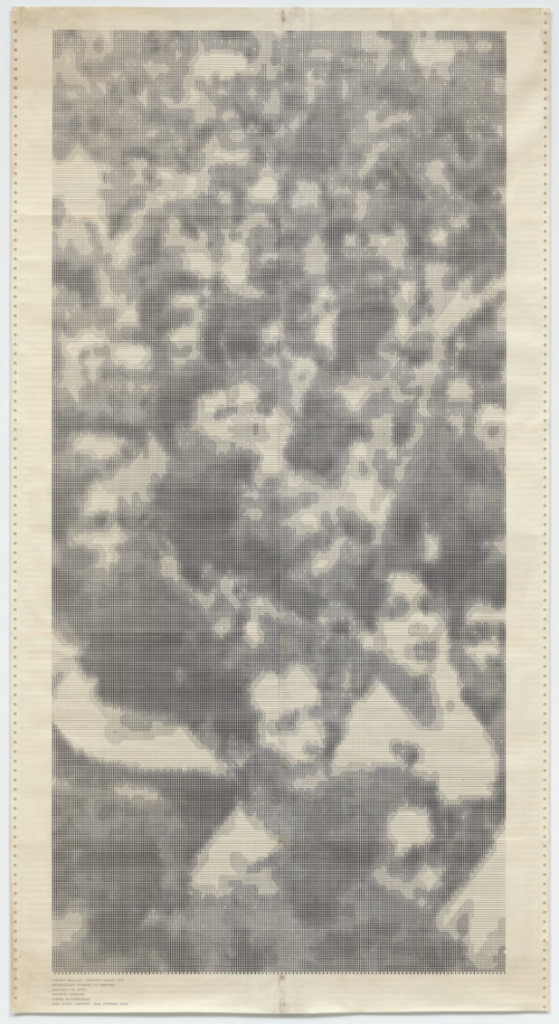

Cordeiro, W., 1972. Gente Ampli2*. [digital print] São Paulo: State University of Campinas.

Waldemar Cordeiro’s Gente Ampli2* (1972) is a computational artwork created by manually digitising a press photograph of a public protest in São Paulo. Cordeiro divided the image into a grid, assigned tonal values to each square, and translated these into symbols representing different shades of grey. The final image was printed using an IBM 360 computer, resulting in a pixelated abstraction of the original scene. This early example of computer-generated art bridges analogue observation with digital output.

The project speaks directly to my area of interest, where I explore the interplay between digital and analogue by using pixelation and translating data into tactile forms. Cordeiro’s hands-on method of digitisation – carefully selecting which values to keep or discard – reflects my own role in editing and shaping data through material processes. The approach to the final piece is deeply physical and humanly deliberate, aligning with my desire to reintroduce human warmth and imperfection to abstractify and change the meaning of systems. Gente Ampli2* reinforces my belief in “hacking” tools or processes to challenge assumptions about technology, authorship, and representation – uncovering not just new aesthetics but new ways of thinking about who has the power and control in data translation.

Generative Knitting, Olivia Glennon

Glennon, O. (2019) Generative knitting, Medium.

This project explores the intersection of data, code, and textile-making by translating photographic information into knit patterns using a hacked 1990s electronic knitting machine. Drawing inspiration from the Jacquard loom and artists like Claire Williams and Anni Albers, the team developed custom software to extract colour palettes from images and map them onto digital knitting blueprints. These patterns were then physically produced with a hacked knitting machine, with the project embracing both the limitations and unexpected outcomes of the medium. The process highlights a curiosity for how digital systems can be reimagined through tactile, imperfect, and materially grounded practices.

This approach closely aligns with my own area of interest: translating digital data into physical forms by “hacking” or repurposing tools in ways they weren’t originally designed for. I’m particularly interested in how this project frames the act of knitting not only as craft but as computation – highlighting the labour, error, and decision-making that challenges digital perfection. It reinforces my project’s belief that analogue processes can offer rich alternatives to screen-based interaction, allowing information to be felt and experienced in ways that are more human, intimate, and materially nuanced.

In Defense of the Poor Image

Steyerl, H. (2019) In defence of the poor image

In In Defence of the Poor Image (2019), Hito Steyerl explores the aesthetics and cultural value of low-resolution digital images – what she calls “poor images.” Far from dismissing them as degraded or failed versions of their high-quality originals, Steyerl argues that these images are cultural artefacts in their own right. The “poor image” is often a by-product of repeated compression, format conversion, or unauthorised circulation. It travels through networks, is re-uploaded, copied, pirated, shared, and stripped of resolution over and over again. Yet, rather than erasing meaning, Steyerl sees this process as adding to the image’s significance. These images gain their political and social power not from clarity or sharpness, but from their accessibility, mobility, and resistance to capitalist structures of controlled distribution.

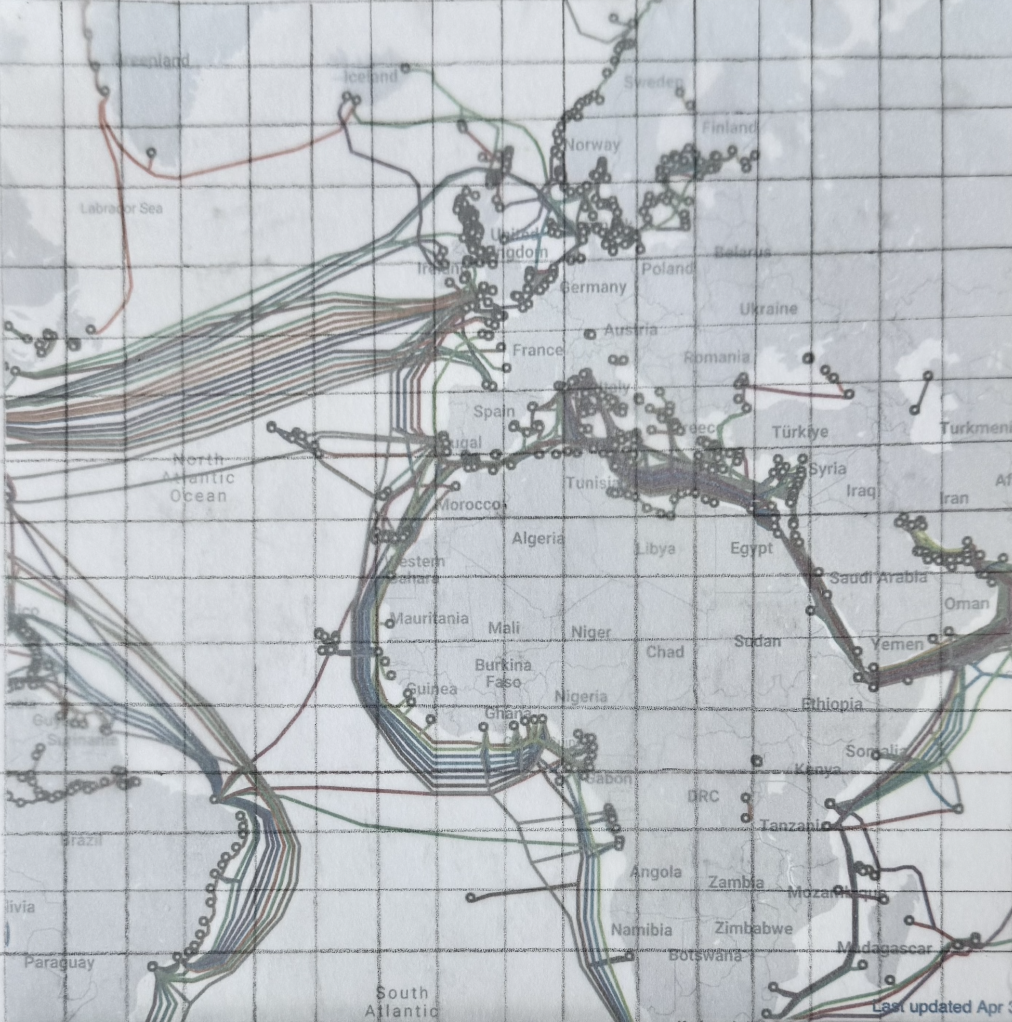

Crucially, Steyerl draws attention to the invisible labour of digital infrastructure – how images constantly travel through undersea cables, servers, and screens, compressed and decompressed by machines at rapid speed. These technical manipulations, largely automated and invisible to us, disconnect the image from its material presence and reduce its perceived value. A poor image, according to dominant cultural standards, is seen as worthless, even though its journey might have been long, charged, and deeply human.

This perspective aligns with and challenges my own practice, which focuses on translating digital data into tactile, physical forms. Steyerl’s text prompts me to ask: What if a human, not a machine, were responsible for the compression of an image? Would that repetition, that labour, add value instead of erasing it? I imagine compressing an image by hand – pixel by pixel, frame by frame – until it blurs beyond recognition. Rather than being dismissed as visual noise, such an image could become a poetic object, rich with evidence of time, attention, and craft.

In a world where data is transmitted constantly and automatically – images flowing through pulses of light across continents – there is something important about pausing to acknowledge the journey. If we knew that an image had travelled across oceans, changed hands, and been altered lovingly or laboriously (even criminally) by people, would we value it more? My practice often seeks to reintroduce this sense of presence, of human intervention, by “hacking” digital tools and repurposing them for analogue expression. I try to take on the role of the computer – not to emulate it perfectly, but to question what gets lost or preserved in translation and putting value to this.

Steyerl’s idea of the “poor image” offers a kind of permission: to embrace degradation, imperfection, and repetition not as loss, but as layers of meaning. By intentionally rendering data imperfect, by allowing handmade processes to intervene in digital areas, I hope to give form to the unseen and give presence to the overlooked. Her writing challenges the assumption that clarity equals quality, and instead opens space for a slower, more embodied, and deeper understanding of image and data.

What to Keep, What to Lose, Shaheer Tarar

Shaheer Tarar’s cross-year presentation What to Keep, What to Lose had a significant impact on the direction of my project. It offered not only a theoretical framework for thinking about digital imagery and data transmission, but also grounded these concepts through hands-on exercises that revealed the often invisible processes behind image compression and digital transformation. What stood out most to me was how clearly it exposed the decisions – both human and algorithmic – that shape the digital visuals we constantly see and take for granted.

The idea that every image is the result of decisions on “what to keep” and “what to lose” resonates strongly with my own work, which explores how digital data can be translated into tactile, human-made forms. During Tarar’s session, we were introduced to the complex layers involved in the digital image pipeline, from binary encoding and light-based transmission via fibre-optic cables, to the various levels of compression that occur along the way. It was highlighted how much information is repeatedly shaved away in this process – lossy compression algorithms deciding, based on pre-set values, which data is worth preserving and which can be discarded. These decisions, while seemingly technical, are ultimately rooted in human biases and priorities, and they shape how meaning is transmitted and received.

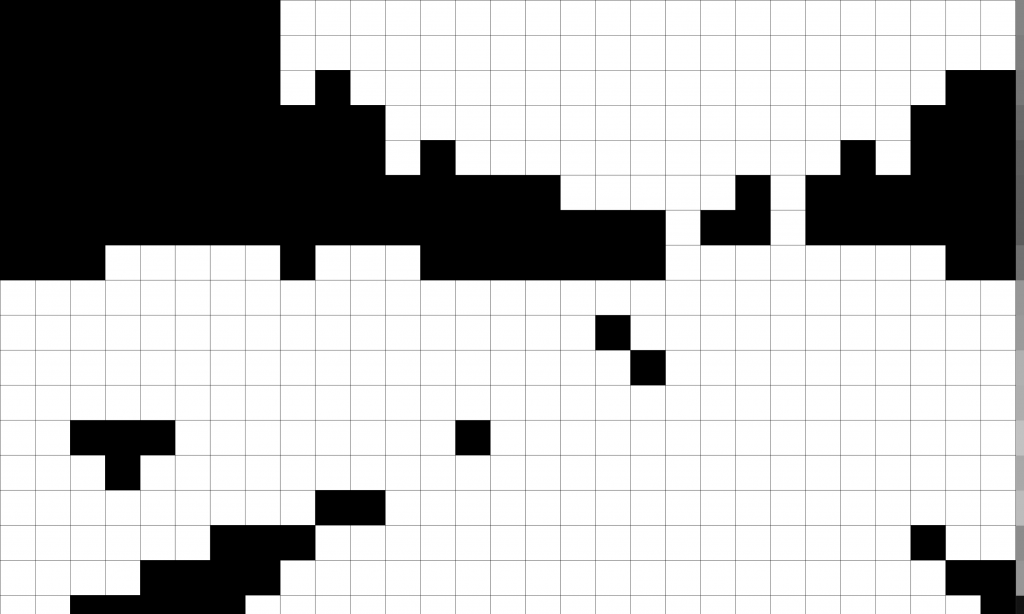

These ideas were then brought to life through the analogue exercises we did. In one, we hand-pixelated a digital image by dividing it into a grid and selecting a single colour to represent each pixel. In my case, I chose the most dominant colour in each square based on intuition and visual judgment. This act mimicked the process computers perform in milliseconds, yet doing it by hand made the process not only labour and time filled but also personal and subjective. It brought to light the fact that compression isn’t just about data loss – it’s also about decision-making and the imposition of value.

Another exercise involved translating a black-and-white photograph into a set of patterns based on the lightness or darkness of each area. We then learnt to develop a code and used a code that used those patterns to reconstruct and increasingly pixelate digital images. As more pattern-pixels were added, the image became more detailed – essentially reversing the compression logic.

These experiments helped me realise how much is lost in translation when machines make aesthetic decisions. They also highlighted a key difference between digital and human processes: time and intentionality. A computer compresses and transmits images at the speed of light, but it seems that the more time a human spends reinterpreting, compressing, and transforming data by hand, the more value it gains – because it tells a story, shows evidence of labour, and carries emotional weight.

This idea directly affects my practice, where I aim to explore the warmth and richness that come from reinterpreting digital processes through analogue, tactile methods. Rather than seeing poor-quality or compressed abstract imagery as loss of value, I am interested in reframing it as material that communicates a story – a trace of journeys through cables, screens, and human hands.